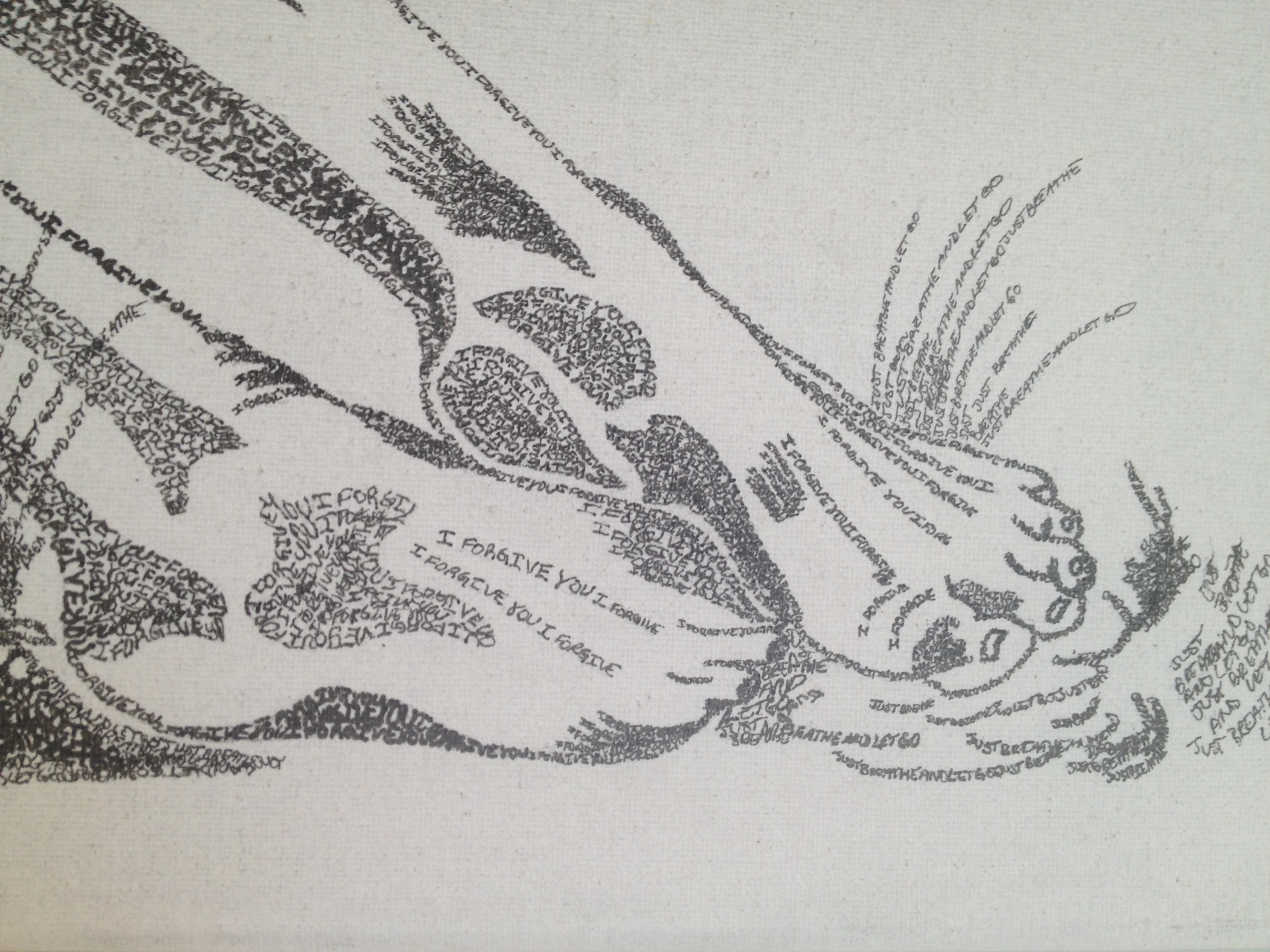

Trauma is the Common Denominator, Healing is the Common Goal

Whether they emerge from the shadow of sexual abuse, the wake of a hurricane, the rubble of a terrorist attack, or the smoke of combat, survivors of traumatic events all have one thing in common — picking up the pieces of a life shattered by violence. Trauma, especially when left untreated, has a devastating impact on the victim’s physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing.

But the problem is not just a private one. Like the shock wave from a bomb blast, the consequences of untreated trauma radiate far beyond an individual ground zero, inflicting damage throughout our society. The affects can be felt from our hospitals and prisons to our schools and businesses — costing our nation billions of dollars annually. With more Americans serving in Iraq and Afghanistan, increasing acts of terrorism, rising crime and the lingering aftermath of hurricanes Katrina and Rita, we face a growing public health crisis caused by trauma that touches us all.

But the problem is not just a private one. Like the shock wave from a bomb blast, the consequences of untreated trauma radiate far beyond an individual ground zero, inflicting damage throughout our society. The affects can be felt from our hospitals and prisons to our schools and businesses — costing our nation billions of dollars annually. With more Americans serving in Iraq and Afghanistan, increasing acts of terrorism, rising crime and the lingering aftermath of hurricanes Katrina and Rita, we face a growing public health crisis caused by trauma that touches us all.

The vast scope and scale of this issue demands our urgent attention. Yet this crisis remains neglected by elected officials, policy makers, and a majority of citizens, due to the lack of public education, awareness, and support for an integrated “trauma informed” approach to assisting the spectrum of survivors.

Solutions exist, as outlined below, following an examination of what trauma is, its human and social costs, the science behind traumatic behavior, and models of therapy. Fortunately, developments in addressing and healing from psychological trauma offer successful methods of coping to those who suffer from natural or man-made violent experiences.

And since trauma is the common denominator of violence and disaster victims, then healing is the common goal we all must share for the sake of our country’s public health and welfare.

Everyone feels “stressed out” at times by seemingly overwhelming situations or has faced some distressful events common to human beings — a fender bender, loss of a job, or death of a loved one. Stress is a part of life.

But trauma from a violent event goes far beyond the average mental, emotional, or physical strain of daily living, leaving the victim with a deeper “silent” wound. For those individuals, the trauma isn’t just part of life, it changes life as it was once known.

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV) defines a “traumatic event” as one in which a person experiences, witnesses, or is confronted with actual or threatened death or serious injury, or threat to the physical integrity of oneself or others. A person’s response to trauma often includes intense fear, helplessness, or sheer horror.[i] Trauma can result from experiences that are “private” (e.g. sexual assault, domestic violence, child abuse/neglect, witnessing interpersonal violence) or more “public” (e.g. war, terrorism, natural disasters).

Medical researchers, sociologists, and healthcare professionals increasingly recognize trauma as a significant factor in a wide range of health, behavioral health, and social problems.[ii] [iii] Trauma resulting from prolonged or repeated exposures to violent events can be the most severe.[iv]

Clearly, different individuals react to trauma in their own way, depending on the nature of and circumstances surrounding their traumatic experiences. For example, trauma associated with repeated childhood physical or sexual abuse can become a central defining characteristic to a survivor’s identity, impacting nearly every aspect of his or her life. Regardless of its cause, trauma is a central mental health concern and a “common denominator” for violence and disaster victims.

Trauma can have severe negative impacts on a person’s physical and emotional state. The most common experiences include flashbacks, emotional numbness and withdrawal, nightmares and insomnia, mood swings, grief, guilt, distrust, and a lack of physical or sexual intimacy. Trauma has been linked to hallucinations and delusions, depression, suicidal tendencies, chronic anxiety and fatigue, hostility, hypersensitivity, eating disorders such as anorexia or obesity, and other obsessive behaviors.[v]

Victims are at a much higher risk for co-occurring mental health disorders and substance abuse, violence victimization and perpetration, self-injury, and a host of other coping mechanisms which themselves have devastating human, social, and economic costs. Trauma has been linked to social, emotional, and cognitive impairments, disease, disability, serious social problems, and premature death.[vi]

In fact, between 51 percent and 98 percent of public mental health clients diagnosed with severe mental illness have trauma histories,[vii] and prevalence rates within substance abuse treatment programs and other social services are similar.[viii] In children, trauma may be incorrectly diagnosed as depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and reactive attachment disorder.[ix] [x] Adults also encounter similar misdiagnosis and obstacles in having their trauma experiences understood and addressed.

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study, which examined the health and social effects of traumatic childhood experiences over the lifespan of 18,000 participants, demonstrated that trauma is far more prevalent than previously recognized, that the impacts of trauma are cumulative, and that unaddressed trauma underlies a wide range of problems. Chronic medical conditions such as heart disease, cancer, lung and liver disease, skeletal fractures, and HIV-AIDS plague many trauma survivors. Also, a host of social ills from homelessness, prostitution, delinquency and criminal behavior, to the failure to finish school or an inability to hold a job, stem from the effects of a traumatic event. [xi] [xii] [xiii] Fractured relationships and support systems also greatly impact the survivor and their ability to heal.

When undiagnosed and untreated trauma manifests itself as civic problems, we all foot the bill. It can significantly increase the use of health care and behavioral health services, as well as boosts incarceration rates and increases the need for victim compensation and services. For instance, we know that more than 40% of women on welfare were sexually abused as children.[xiv] So taxpayers then pick up the tab for the greater reliance on public resources such as Medicare, Medicaid, and other welfare programs, plus the strain on the law enforcement, court, victim service, and prison systems. Meanwhile trauma costs business and the American economy in decreased productivity and unemployment payments.

And the financial burden to society is staggering. The economic expenditures of untreated trauma-related alcohol and drug abuse alone were estimated at $160.7 billion in 2000.[xv] The estimated cost to society of child abuse and neglect is $94 billion per year, or $258 million per day.[xvi] For child abuse survivors, long-term psychiatric and medical health care costs are estimated at $100 billion per year.[xvii] Lost productivity from violence accounted for $64.4 billion annually, with another $5.6 billion spent in medical care.[xviii]

Research on the consequences of recent public disasters, including the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, the 2002 Challenger disaster, the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, and hurricanes Katrina and Rita illustrates that disasters can induce severe and long-term trauma, particularly in those with prior histories of mental health problems, addiction, or trauma.[xix] [xx] [xxi] All disaster victims are likely to experience some form of trauma. While many disaster survivors “recover” from grief and shock after a few months, 25 percent to 30 percent of those directly affected may develop full-blown Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD),[xxii] [xxiii] with the surfacing of increased substance abuse, child abuse taking place months later. Domestic violence incidents can increase 30 percent to 50 percent within three to six months following a disaster in those communities affected.[xxiv]

People with severe mental illness, addictions, and previous histories of trauma are particularly vulnerable to the psychological impact of disasters.[xxv] [xxvi] People with prior exposure to domestic violence (including physical or sexual abuse) in childhood or adulthood have significantly heightened susceptibility to severe and chronic PTSD following exposure to any type of traumatic event.[xxvii] [xxviii] [xxix] Similarly, refugees who had been previously traumatized in their native countries and who had been diagnosed with PTSD are at risk.[xxx]

For those with previous trauma histories, PTSD symptoms, and/or substance abuse problems, trauma symptoms can actually increase with time following a disaster. Often they are able to maintain stability during the initial crisis, but after the immediate crisis passes, they may re-experience thoughts, emotions, symptoms, and anxiety levels like those associated with their previous traumas, causing a kind of “relapse,” increased demand on mental health services, and increased suicide rates.[xxxi] [xxxii]

Especially when experienced in childhood, trauma produces neurobiological impacts on the brain, causing dysfunction in the hippocampus, amygdala, medial prefrontal cortex, and other limbic structures.[xxxiii] [xxxiv] When confronted with danger, the brain moves from a normal “information-processing” state to a survival-oriented, reactive “alarm state.” Trauma causes the body’s nervous system to experience an extreme adrenaline rush, intense fear, problems processing information, and a severe reduction or shutdown of cognitive capacities, leading to confusion and a sense of defeat.

If there are insufficient biological or social resources to assist in coping, the “alarm state” may persist even when the immediate danger has passed, and this can lead to PTSD. Excessive and repeated stress causes the release of chemicals that disrupt brain architecture by impairing cell growth and interfering with the formation of healthy neural circuits. When trauma occurs repeatedly, permanent changes in the brain can occur, compromising core mental, emotional, and social functioning – and resulting in a brain that is focused on simply surviving trauma.[xxxv]

However, recent research suggests post-traumatic stress is not a permanent neuropsychological condition, but rather a functional and largely reversible distortion in the multi-dimensional pathways that meld the mind and body. These discoveries, together with a range of new therapy approaches, are opening new perspectives on healing,[xxxvi] and new treatments are being explored within this context.

Today, the healing journey includes a variety of models and programs offering greater opportunities to trauma victims for health and wellness. Treatment may range from very trauma-specific interventions, to peer support, or to more proactive efforts, such as teaching resilience and coping skills as part of school health education.

Trauma-specific interventions are just that — treatment especially designed to address the consequences of trauma in the individual and assist in healing. Such programs generally acknowledge the survivor’s need to be respected, informed, included, connected, safe, and hopeful regarding their own recovery. Thus, key components involve listening, education, reassurance, and a healing environment. These models recognize the interrelation between trauma and its symptoms (substance abuse, easting disorders, depression, anxiety, etc.). They also understand the need to work in a collaborative way with survivors, as well as their families and friends, and integrate other human services agencies in a manner that empowers survivors. Some of the well-known trauma specific interventions include the Sanctuary Model, Essence of Being Real, Seeking Safety, Risking Connection, Addition and Trauma Recovery Integration Model (ATRIUM), and the Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model (TREM).[xxxviii]

Peer support, as a therapeutic model, has recently proven to be an innovative, successful, and cost-effective approach in response to disaster trauma. It is based on the simple principle that those who have previously experienced a traumatic event and have used mental health services in their recovery are well equipped to help others face the same challenges. In fact, it’s been shown that the shift from a passive victim to a proactive survivor offering leadership and support plays a valuable role in the peer-provider’s own relief from trauma. In addition, peer-counselors help reduce the burden on the often undersized, overwhelmed professional staff. These peer-based programs emphasize outreach, focus on people’s strengths, avoid mental health labels, occur in local settings, offer social support, and are more culturally sensitive because they are delivered by people who are themselves community members. Notable examples of successful peer-support programs include Oklahoma City following the Murrah Building bombing, New York City after 9/11, and Louisiana in the wake of hurricanes Katrina and Rita. [xxxix] Many states are still in the early stages of developing a network of peer-support services in preparation for disasters, and unfortunately, no peer response model currently exists for those trauma victims in the criminal justice area.

Resilience development is another exciting, proactive innovation for the prevention as well as treatment of trauma. Dennis Charney, M.D., Ph.D., dean of research and professor of psychiatry at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, believes that through focused training and cognitive behavioral therapy, people can be inoculated against stress. “You can learn to recognize your own character strengths and engage them to deal with difficult and stressful situations,” he notes. Charney and Yale psychiatry professor Steven Southwick, M.D., identified personality traits associated with resilience in 250 American POWs held captive for up to eight years in the Vietnam War, who were subjected to torture and solitary confinement. Then in two other studies, they interviewed women who had suffered severe trauma from sexual and physical abuse, and a group of people who displayed courage and resilience in the face of serious medical problems. All three groups shared the same characteristics of resilience: optimism, cognitive flexibility, altruism, strong or heroic role models, adeptness at facing fears, physical fitness, a supportive social network, active coping skills, a sense of humor, and a personal moral compass or shatterproof set of beliefs. Fostering those characteristics will help people deal with adversity when it occurs and recover faster from a traumatic event.[xl]

Recent public disasters, such as 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, have provided a new sense of urgency for the long-standing need for trauma education and awareness-building among all organizations, institutions, and agencies that come into contact with survivors of violent events.

When a program moves toward becoming trauma informed, every part of its organization, management, and service delivery system is assessed and potentially modified to include a basic knowledge of how trauma impacts the life of the individual seeking help. Trauma informed systems are based on an understanding of the vulnerabilities or triggers of trauma survivors that traditional approaches may actually aggravate or intensify, making this new generation of programs more supportive and less likely to re-traumatize the victim.

This is necessary to promote the health and wellbeing of survivors and their families, and to set the stage for health and mental health professionals, organizations providing services to trauma survivors, law enforcement and criminal justice officials, emergency responders, and others to effectively and seamlessly integrate trauma understanding into their existing programs and procedures.

And there is no time to lose in developing trauma informed solutions for the growing population of violence and disaster victims. In a Sept. 29, 2006, letter to President Bush, the U.S. House of Representatives Bipartisan Caucus on Addiction, Treatment, and Recovery stated:

“It has become more clear than ever psychological trauma is a primary — but often ignored or overlooked — factor of health (both physical and mental) with which survivors of violent crime, abuse, disaster, terrorism and war must contend, and this presents a public health crisis in the United States that needs to be addressed immediately.”

Advocacy is not only needed to educate are raise awareness on the issue, but also for:

- Legislators to consider how psychological trauma may play a role in pending or future legislation, including policy that addresses disaster preparedness and response, national defense and our armed forces, plus initiatives on crime (domestic violence, sexual assault, stalking, child abuse/neglect), mental health, education, homelessness, and more

- Inclusion of programs, services, and funding in legislation that addresses trauma and provides short-term, intermediate, and long-term support through the healing process

- Development and implementation of prevention measures, such as peer-support service networks and resilience training education

- More support for efforts that address psychological trauma through new models with proven track records of success, such as peer-support

Authored by Helga Luest © 2007 Witness Justice/Helga Luest

———————————

[i] American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM IV-TR), fourth edition. Washington, DC: APA.

[ii] Felitti, V. J. (2003). The Relationship of Adverse Childhood Experiences to Adult Health Status. Presented September 2003 at the “Snowbird Conference” of the Child Trauma Treatment Network of the Intermountain West. DVD published by The National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

[iii] Felitti, V., Anda, R., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D., Spitz, A., Edwards, V., Koss, M., Marks, J. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258.

[iv] National Child Traumatic Stress Network Complex Trauma Task Force (2003). Complex trauma in children and adolescents: white paper.Eds. Cook A., Blaustein, M., Spinazzola, J., vanderKolk, B.

[v] Mueser, KI., Rosenberg, S., Goodman, L., & Trumbetta, S. (2002). Trauma, PTSD, and the course of severe mental illness: an interactive model. Schizophrenia Research, 53, 123-143

[vi] Anda, R., Felitti, V., Walker, J., Whitfield, C., Bremner, J., Perry, B., Dube, S., Giles, W. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. (Submitted for publication) (ACE Study).

[vii] Mueser, K., Goodman, L.A., Trumbetta, S.L., Rosenberg, S.D., Osher, F.C., Vidaver, R., Auciello, P., & Foy, E.W. (1998). Trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 493-499.

[viii] Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2000). Substance abuse treatment for persons with child abuse and neglect issues Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) series. (DHHS Publication No. SMA 00-3357, Number 36. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

[ix] The Science of Early Childhood Development: Closing the Gap Between What We Know and What We Do. Jack P. Shonkoff, Dean of the Heller School for Social Policy and Management, and Chair of the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Presentation to the 15th National Conference on Child Abuse and neglect, Boston, MA April 19, 2005. Powerpoint: National Scientific Council on the Developing Child.

[x] Cook, A., Blaustein, M., Spinazzola, J., and van der Kolk, B. (2003). Complex trauma in children and adolescents: White Paper from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network: Complex Trauma Task Force.

[xi] Felitti, V., Anda, R., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D., Spitz, A., Edwards, V., Koss, M., Marks, J. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258.

[xii] Felitti, V. J. (2003). The Relationship of Adverse Childhood Experiences to Adult Health Status. Presented September 2003 at the “Snowbird Conference” of the Child Trauma Treatment Network of the Intermountain West. DVD published by The National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

[xiv] Mueser et. al., in press; Mueser et. al.(1998).

[xv] The Economic Costs of Drug Abuse in the United States 1992-1998. Report prepared by The Lewin Group.

[xvi] Prevent Child Abuse America. (2001). Total estimated cost of child abuse and neglect in the United States: Statistical evidence. Report funded by the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation.

[xvii] The Ross Institute (www.rossinst.com)

[xviii] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study, published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine (June 2007)

[xix] Galea, S., Ahern, J., Resnick, H., Kilpatrick, D., Bucuvalas, M., Gold, J., & Vlahov, D. (March 28, 2002). Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 346, No. 13, pp. 982-987

[xx] Terr, L. C., Bloch, D. A., Michel, B. A., Shi, H., Reinhardt, J. A., & Metayer, S. (1999). Children’s symptoms in the wake of Challenger: a field study of distant-traumatic effects and an outline of related conditions. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 1536-1544.

[xxi] Breslau, N., Chilcoat, H. D., Kessler, R. C., Davis, G. C. (1999). Previous exposure to trauma and PTSD effects of subsequent trauma: Results from the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156:902-907.

[xxii] North, C.S. (2001). The course of post-traumatic stress disorder after the Oklahoma City bombing. Mil Med, 166 (12 Suppl): 51-2

[xxiii] Abenhaim, L., Dab, W., & Salmi, L. R. (February 1992). Study of civilian victims of terrorist attacks (France 1982-1987). Journal of Clinical Epidemiol, 45(2);103-9.

[xxiv] Norris, F. H. Prevalence and impact of domestic violence in the wake of disasters. A National Center for PTSD Fact Sheet. (See www.ncptsd.org/facts/disasters/fs_domestic.html)

[xxv] North, C., Nixon, S., Shariat, S., Mallonee, S., McMillen, J., Spitzanagel, E., & Smith, E. (1999). Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. Journal of the American Medical Association, 282, 755-762.

[xxvi] Mueser, K. T., Trumbetta, S. L., Rosenberg, S. D., Vidaver, R. M., Goodman, L. B., Osher, F. C., Auciello, P., Foy, D. W. (1998). Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(3), 493-499.

[xxvii] North, C., Nixon, S., Shariat, S., Mallonee, S., McMillen, J., Spitzanagel, E., & Smith, E. (1999). Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. Journal of the American Medical Association, 282, 755-762.

[xxviii] King et al. (1999). Stretch, Knudson, & Durand (1998). Bremner, Southwick, Brett, & Fontant (1992). Breslau et al. (1998). Green et al. (2000). Nishith, Mechanic, & Resnick (2000). In B. Litz, M. Gray, R. Bryant, & A. Adler. Early intervention for trauma: Current status and future directions. A National Center for PTSD Fact Sheet. See www.ncptsd.org/facts/disasters/fs_earlyint_disaster.html

[xxix] Breslau, N., Chilcoat, H. D., Kessler, R. C., Davis, G. C. (1999). Previous exposure to trauma and PTSD effects of subsequent trauma: Results from the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156:902-907.

[xxx] Kinzie, J. D., Boehnlein, J. K., Riley, C., Sparr, L. (July 2002). The effects of September 11 on traumatized refugees: Reactivation of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis, 190(7):437-41

[xxxi] Nader, K. (1998). Violence: Effects of a parents’ previous trauma on currently traumatized children. In Y. Danieli (Ed.), An international handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma (pp. 571-583), New York, NY: Plenum Press.

[xxxii] Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., Valentine, J. D. (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68:748-766.

[xxxiii] Hull, A. (2002). Neuroimaging findings in post-traumatic stress disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 181, 102-110.

[xxxiv] Van der Kolk, B., Pelcovitz, D., Roth, S., Mandel, F., McFarlene, A., Herman, J. Dissociation, affect dysregulation and somatization: The complex nature of adaptation to trauma. May 2005

[xxxv] Anda, R., Felitti, V., Walker, J., Whitfield, C., Bremner, J., Perry, B., Dube, S., Giles, W. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. (Submitted for publication) (ACE Study).

[xxxvi] Bessel van der Kolk. (2002) In Terror’s Grip: Healing the Ravages of Trauma. Cerebrum, 4, 34-50. NY: The Dana Foundation.

[xxxvii] Peter A. Levine, Ph.D. (1997) Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma: The Innate Capacity To Transform Overwhelming Experiences. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books.

[xxxviii] The National Center for Trauma Informed Care, www.mentalhealth.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma.asp

[xxxix] Daniel F., Rote K., Miller L., Romprey D. and Filson D. From Relief to Recovery: Peer Support by Consumers Relieves the Traumas of Disasters and Recovery from Mental Illness. Resource paper presented at the After the Crisis: Healing from Trauma after Disasters meeting, April 24-25, 2006, Bethesda, Md. Updated July 2006.

[xl] “People Can Learn Markers on Road to Resilience,” Psychiatry News, January 19, 2007, Vol. 42, No. 2, p. 5.